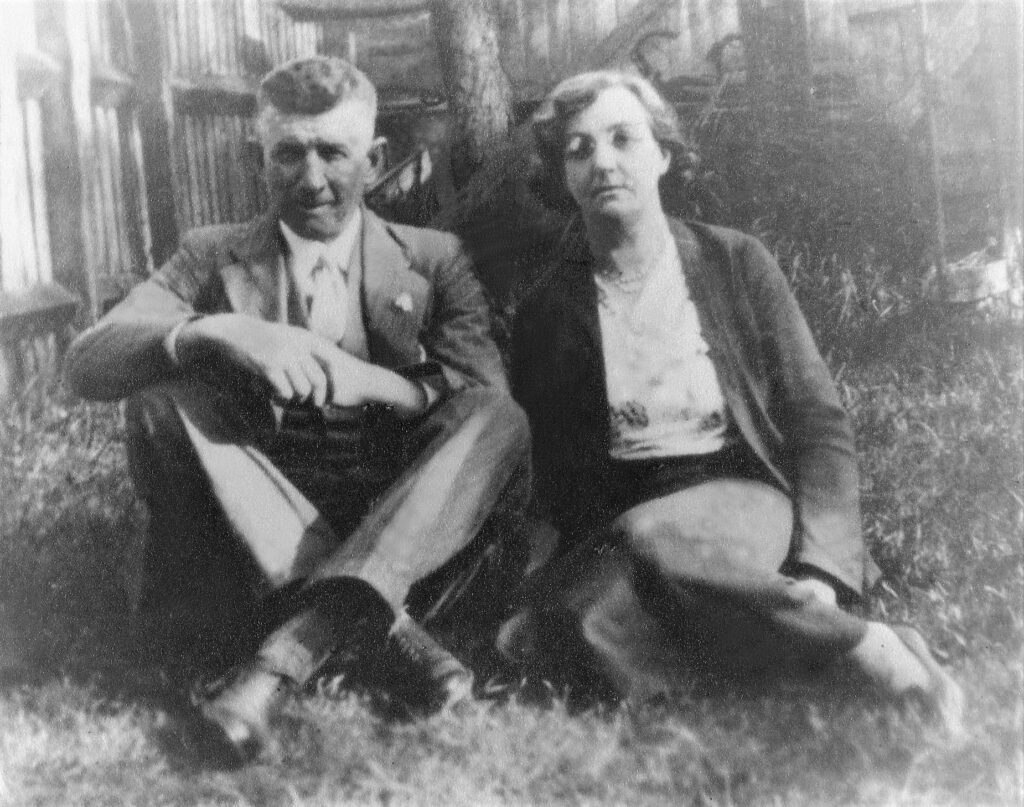

Robert Charles Henry Green, was born to Mother Gwendoline (nee Cave), and Father George Harry, on 19th November 1918, just over a week after Armistice Day, at 14, Clinton Lane, where they rented a room. This was at a time of no NHS, and when home births were common practice.

Prior to living at Clinton Lane, they had lived at the King’s Arms Hotel in Warwick Road, where George Harry, WW1 veteran, was employed as a ‘Boots’.

Little did this family know that in just over twenty year’s time, they would again, be involved in another World War. When Robert was two-years-old the family moved again, this time into a council house at 68, School Lane (opposite the Chip Shop).

During 1938/39, it was obvious to everybody (except Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain apparently) that World War Two was coming along, sooner or later.

Robert didn’t much fancy conscription into the Infantry when war did arrive, so he decided to find an alternative combat role, and the Artillery fitted the bill. So in March 1939, he made the decision to join-up.

He walked into the headquarters of the Territorial Army of the 271st (Warwick) Field Battery, Royal Artillery at Clarendon Place, in Leamington Spa, and signed on the dotted line.

He was now a ‘Gunner’ in the Royal Warwick’s, but his plan on keeping out of the frontline backfired on him as he was eventually deployed as a ‘Signaller/Driver’ for the 271st Battery, a job which directed fire from the frontline with the infantry!

As we all know, World War Two was declared on 3rd September 1939, when Neville Chamberlain made that famous speech on the radio, but orders had already been given to 271st Battery, two days earlier to report for duty as soon as possible to Clarendon Place. Two weeks later, his regiment was mobilised, and they moved south to Swindon, where they trained for several weeks, in readiness for war.

British Expeditionary Force

Aged 21, Robert was part of the BEF (British Expeditionary Force), that was sent to France to tackle the Germans. He sailed with the 68th (South Midland) Field Regiment, which included two Field Batteries, his 271st, based at Leamington/Rugby, and their sister Battery, the 269th from Birmingham. They were both part of the 48th (South Midland) Division.

Robert eventually set sail for France in January 1940, and docked at La Havre, and was met by snow and freezing conditions. The Regiment then travelled to Bolbec about 20 miles away, here the 271st Battery, were allocated farm buildings to bed down for the night, and a cold night it was too. They all used hay as improvised mattresses. The following day, they travelled 130 miles south to Lallaing, near Douai in the Nord region. With temperatures still well below freezing, and snow continuing to fall, the journey was extremely hazardous. Robert’s battery was billeted in the nearby village of Anhiers,which was a coal mining district. Their first night was spent in some derelict buildings in a disused colliery. A night, no one was likely to forget as they slept on steel floors, in sub zero temperatures. Not much slept was had by anybody. Thankfully however, they were soon found accommodation at local private houses. The weather was so cold, that the radiators on their vehicles, had to be drained every night to prevent the water freezing and cracking the engine blocks.

The Germans were obviously waiting for better weather before they attacked, and even though conditions improved during March, nothing yet had happened. In the meantime the 271st Battery, and the regiment continued with various types of training, including marches, gun drills, vehicle maintenance and lectures etc. They even had French lessons.

WW1 Equipment

Robert’s war had started slowly, but the 271st Battery, like much of the BEF weren’t really equipped for modern warfare against the heavily armed, and modernised Germans Forces. They only had one rifle per five men, and they had to use 18 Pounder Artillery pieces from the First World War, which were stamped ‘1917’. Not only did they still have First World War equipment.

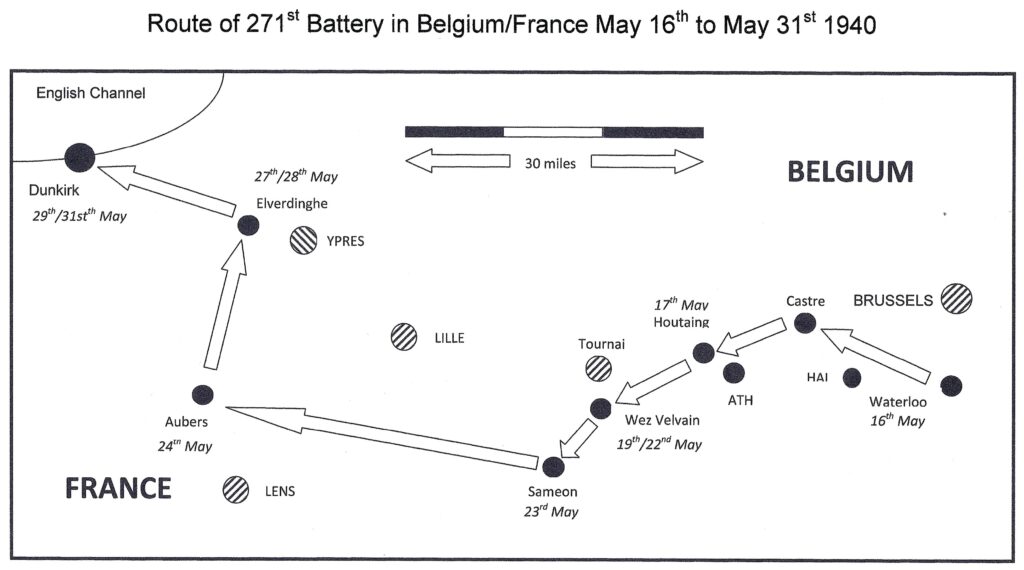

The Germans finally attacked Holland, and Belgium on 10th May. The Battery was first called into action in Belgium, when supporting the 145th Infantry Brigade on 16th May at Waterloo, south of Brussels. But there was no enemy contact that day, as the Belgium Army were just about holding back the Germans, so they withdrew 15 miles to Castre near Hal, leaving the Belgium’s to their fate. No sooner had they ‘dug in’ when they were on the move again. So, on 17th May, they moved a further 20 miles to Houtaing, west of Ath, to counteract the anticipated threat of enemy armoured vehicles that had crossed the River Deindre. Once again, they did not fire a shot, and moved another 20 miles, to positions at Wez Velvain near Tournai. It was here on 19th May, that Robert had his first battle, when he directed fire in support of the 144th Infantry Brigade, when they were holding a stretch of the River Escault. Under heavy shelling, they held this position until 22nd May, but the situation was rapidly deteriorating, so they had to drop back to Sameon, just inside the France border.

Rapid Withdrawal

The Nazi Blitzkrieg (Lightening War) was now unstoppable, so a rapid withdrawal became the only option for the BEF, but the awful road congestion due to fleeing soldiers, and refugees made it difficult. Troop movement was done mainly at night, to avoid the Stuka and Messerschmitt aircraft, but this had its own problems. Travelling by night, and fighting by day, meant that troops were getting no proper rest or sleep. Drivers including Robert, were literally falling asleep at the wheel, and accidents did occur especially as they were travelling so close to the vehicle in front, without lights. Lights were not allowed to be used on vehicles as this could have given their position away. If a vehicle stopped quickly a domino effect of collisions would occur.

Click on image to enlarge

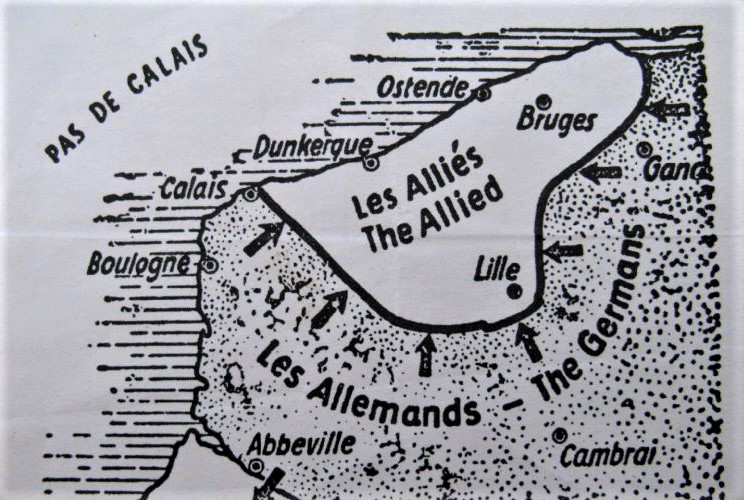

By the 24th May, the Battery had moved to the south west of Lille, to halt the German forces advancing from the south. Matters were not helped, when it was reported that the Belgium Army, had capitulated on the 26th May, which left the BEF exposed. The next day, they were pushed back again, this time 25 miles northwards to Elverdinghe, near Ypres. Here, they occupied their final positions, and on 29th May, they fired their last rounds of ammunition. Orders came through, to head towards the coast for evacuation. Calais and Boulogne had fallen, so the only port available to the BEF was Dunkirk, where literally thousands of allied troops were already congregating on the beaches, in the hope of being shipped back to England.

After destroying their guns, and trucks so that the enemy could not make use of them, the 271st Battery, walked the last few miles under continuous harassment from enemy aircraft. Trucks were destroyed by draining the oil, and running the engines until they seized, they were then set on fire. Guns were blown-up by putting an explosive charge in the breech.

On their journey to the coast, the 271st Battery could see the destruction that the Luftwaffe had brought upon the country. Towns and villages, that had deliberately been targeted, lay in rubble. Many of their civilians now with no homes left, also headed towards the coast, hopeful maybe, of escape themselves. Such was the chaos, and confusion, Robert somehow became detached from his battery, but made his way to Dunkirk, with just a handful of his comrades.

Arrival at Dunkirk

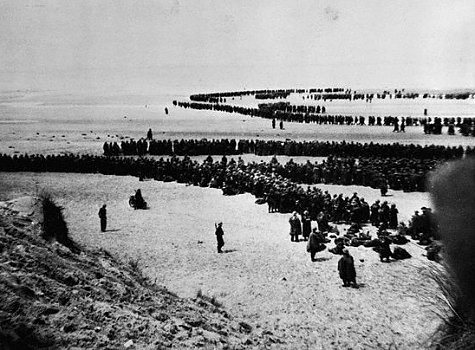

On arrival at Dunkirk, Robert could see the full extent of the trouble the BEF were in. As far as the eye could see, troops in their thousands spread along the beach, in all directions. Men in orderly lines, stretched down to the beach, and into the sea up to their necks to await embarkation. Looking along the beach towards Dunkirk Harbour where the bulk of troops were amassed, black plumes of smoke could be seen, belching out into the sky, for many a mile, where the fuel dumps were on fire.

On the beaches, the troops were totally exposed, with no cover at all. Straight away Robert went up in the dunes, and dug himself a six foot deep trench. The softness of the sand offered some protection against bombs, as only a direct hit or a very near miss would cause injury. The blast would be absorbed, so less shrapnel was scattered.

One of the most terrifying moments was when Messerschmitt’s flew parallel to the beach, strafing machine gun fire into the troops. After three long days on the beach, it was Robert’s turn to leave his trench, and join the queue to get on a ship but troops became more vulnerable out in the open beach.

The Germans were not only bombarding the BEF with shells, bombs and bullets, but with propaganda leaflets as well. They strongly advised the British (and their Allies) to put down their arms as they were entirely surrounded. However, this advice was not taken. The troops found these leaflets made excellent toilet paper.

The beaches at Dunkirk had long gradual slopes, so large naval craft could not get near to the troops. Various ideas were put into place to get troops out to the ships, one was to drive vehicles out at low tide and lined them up nose-to-tail, to form a type of pier, men could then walk across the roofs, and get closer to the ships. The evacuation became famous for all the small boats that sailed over, to ferry the troops from the beaches to ships lying off shore. This came about when an SOS was sent out to all owners of small boats between 30 feet and 100 feet in length, to help with the evacuation, known officially as operation ‘Dynamo’. Hundreds of these civilian craft including tugboats, motor yachts and cruisers, eventually came to the aid of the BEF, and played a significant part in the operation. Around a third of the total troops evacuated from Dunkirk, can thank these small craft for their safe return.

However, Robert was on a stretch of beach where not many small boats were present. So, in the afternoon of 31st May, he waded out up to his neck, and had no option, but to swim to a destroyer, and scramble aboard. Luckily, during the evacuation, the weather was excellent, and the flat-calm conditions, were a godsend.

Destroyers were a prime target for the Stuka dive bombers, especially as there were so many troops on board, and on several occasions they attacked the destroyer Robert was aboard, but luckily the bombs missed their target.

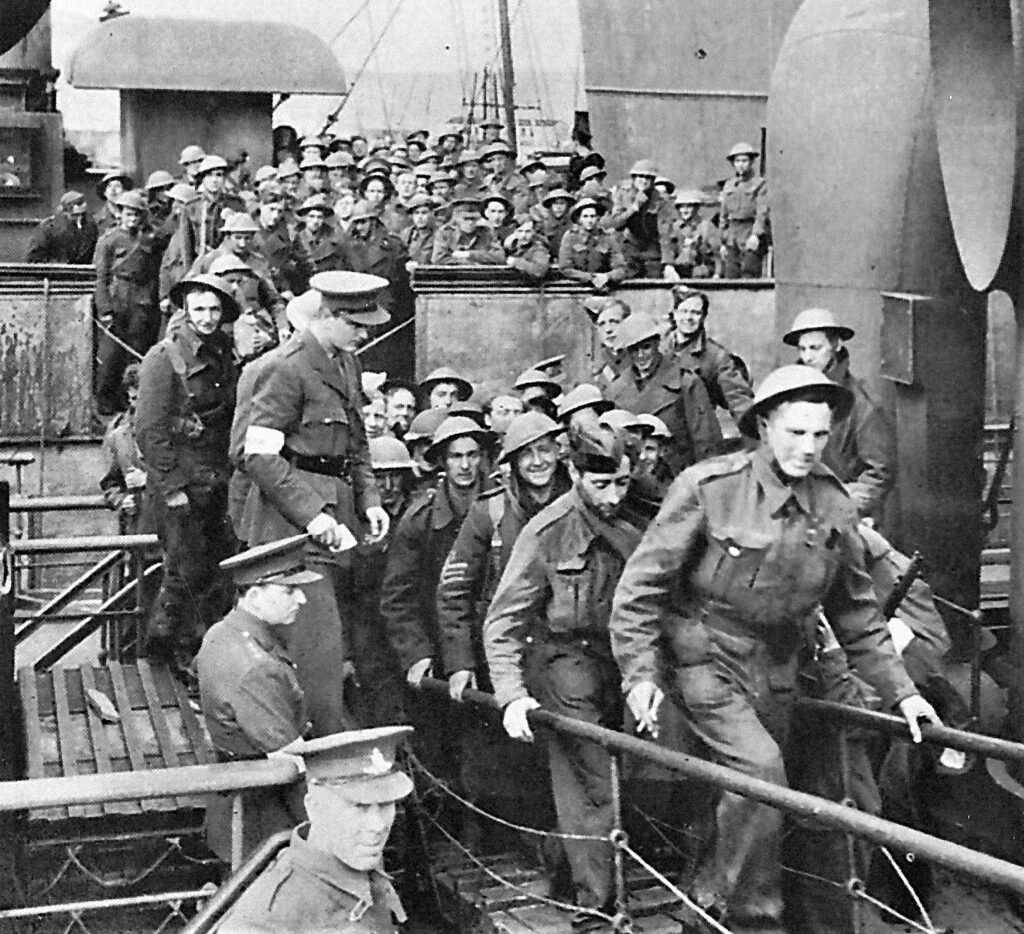

On the day of Robert’s evacuation (31st May), a total of 68,014 men were rescued from the beaches, and harbour at Dunkirk, the highest daily total during the operation. The final count during the nine day evacuation was a staggering 338,226, far more than originally estimated.

It was later discovered that the German High Command had halted their Panzer Divisions for a three days from 24th May, when they got to the River Aa, west of Dunkirk. We can only guess, what would have happened to the BEF, if the Panzers had continued their onslaught. Historians to this day, still debate why this happened.

Daily Totals Evacuated from Dunkirk

| Date | From Beaches | From Harbour | Daily Total |

| Mon 27 May | – | 7,699 | 7,699 |

| Tue 28 May | 5,930 | 11,874 | 17,804 |

| Wed 29 May | 13,752 | 33,558 | 47,310 |

| Thu 30 May | 29,512 | 24,311 | 53,823 |

| Fri 31 May | 22,942 | 45,072 | 68,014 |

| Sat 1 June | 17,348 | 47,081 | 64,429 |

| Sun 2 June | 6,695 | 19,561 | 26,256 |

| Mon 3 June | 1,870 | 24,876 | 26,746 |

| Tue 4 June | 622 | 25,553 | 26,175 |

| TOTAL | 98,671 | 239,555 | 338,226 |

Although the RAF gave good air support over the English Channel, it was still a tense and nervous crossing due to the constant threat of being torpedoed. Robert, unshaven, exhausted and starving, eventually landed at Dover late into the evening. After a cup of tea, and some food, he was sent by train to Bovington Camp in Dorset, for some much needed R&R, where he apparently slept for nearly two days!

Robert went on to serve in North Africa, the Middle East and Italy. His last battle of the war, was in Italy on 20th April 1945, near Fiorentina, when they were in support of the 1st and 2nd Punjab’s, whose mission it was to cross the River Idice. It was here in Italy, just over two weeks later, that the 271st Battery celebrated VE day.

Due to Robert’s reserved occupation as a Gas Fitter, (he worked at the Gas Works at Mill End) he was discharged in December 1945. He was safely back in Kenilworth, after a long and gruelling adventure. Robert re-enlisted in the TA until 1949, and in total, he was in the Artillery for just over 10 years.

On leave in 1942, Robert, “Bob” to his friends had met 17-year-old Doreen Beryl Jackson from Edgbaston, who was staying next door to him at School Lane in Kenilworth. After proposing to her on the pier at St Ives, they married in January 1946 at the Methodist schoolroom, Stirling Road in Edgbaston. The schoolroom was used because the church was bombed out. Their marriage produced two children, and two grandsons.

Robert Died in 2008, aged 89, and Beryl in 2019, aged 94.

HI, I’m very interested in Robert Green’s story, as his wartime experiences in the BEF very closely mirror my Uncle’s own which I am trying to better understand. He too was in the 271st battalion, (68th Field) and most likely the Rugby branch. We know he was evacuated from Dunkirk on 31st May, aboard the minesweeper Gossamer. He rarely spoke of his time in France or afterwards, where he spent the rest of the war developing radar as an electronics graduate. I’d be particularly interested in any battalion photographs you may have, as we have found nothing of this kind. Thanks! Gordon.

Hello Gordon

Thanks for your message and interest in my father’s story of escaping from Dunkirk.

It cannot be a coincidence that your uncle and my dad were evacuated from beaches on the same day can it? But then again, a lot of men were evacuated on that particular day.

It also makes me wonder if they came back on the same ship as well, my father never named the ship that bought him home.

The only photo I have of the 271st are scans that I have taken from a book called ‘Before The Echoes Die Away’ by NDG James 1980.This covers both the 271st and the 268th. IBSN 0 9506911 0 0.

Its a book my father bought during one of his annual re-unions at the Royal Spa Centre, Leamington, which hwe attended for many years up until the 1990’s.

They called themselves the ‘Q’ Club, which I believe may have come from them being named ‘Q’ battery, but I’m not entirely sure about that.

Regards

Nick Green