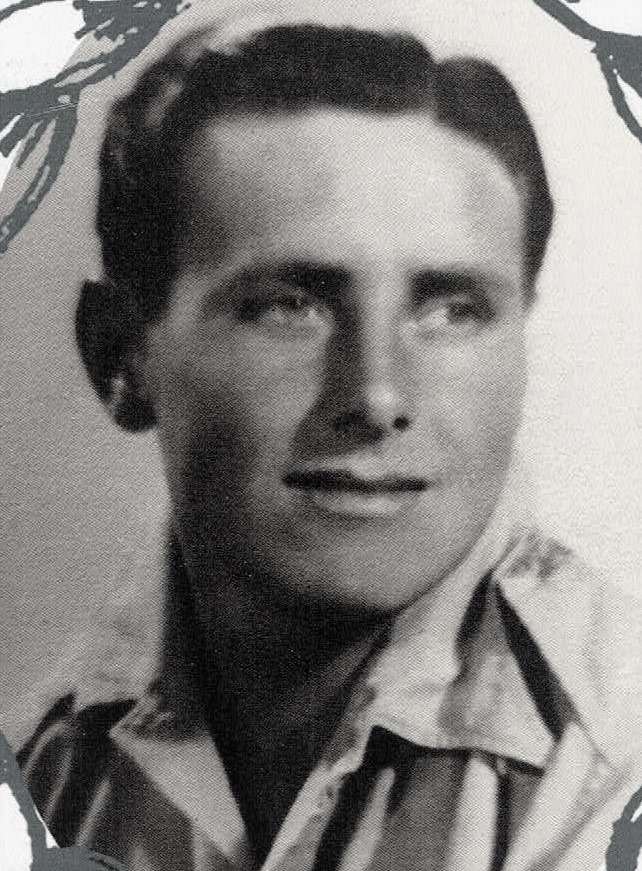

The war of James Walter Lewis, began when a letter dropped through the letterbox of his house in Watling Road, at the beginning of May 1940. It was from the War Office, ordering him to go to the Swift Skating ring in Coventry, for a medical. He duly attended, and was passed A1, and finally on 30th May (at the height of the Dunkirk evacuation), he received his ‘Call Up’ papers.

Jim joined the newly formed 12th Battalion of the South Staffordshire Regiment, whose headquarters were at Lichfield. He was issued with a travel warrant and a 1/- (5p) postal order (the King’s shilling), and his destination was Hanley, Stoke-on-Trent. He caught the train from Kenilworth Station early one morning, and as the train went over the bridge at the bottom of Watling Road, his mother was there waiting for him, to wave him goodbye, and good luck. From this moment on, Jim would be constantly on the move.

Jim’s first stop, was at Birmingham Station, where he was confronted by hundreds of other men, who had also been recruited into this new battalion. They boarded another train and arrived at Hanley to be met by several regular soldiers and an officer. They all walked a couple of miles into the town to the depot that had been allocated for them. Here they were given a meal, a uniform, a mess tin and a bandage pack. Another train was boarded, and they eventually ended up at a stately home near Blandford in Dorset. Here, they started their basis training, and were issued with .303 Royal Enfield rifles.

After spending a couple of weeks in Dorset, the battalion was on the move again, to Burnham-on-Sea, just south of Weston-Super-Mare, in Somerset. But the battalion was quickly moved again, this time to Yorkshire to start firearms training on the .303 rifles. Jim turned out to be a crack shot, hitting 5 bulls out of 5 at his first attempt! His officer was so delighted in his performance, that he persuaded the other platoons to have a competition amongst themselves, and you’ve guessed it, Jim’s ‘A’ platoon won.

At this point the 12th Battalion was split into various units and Jim was placed in the 91st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, and was now part of the Royal Artillery. They were given the task of training on the 40mm, Swedish made Bofors guns. The officers of the regiment noticed Jim’s leadership potential, and promoted him firstly to Lance Corporal, and then to Bombardier (Corporal) and finally to a War Sergeant (Full Sergeant). Jim was now in charge of the regiment’s Gun No.6. Bofors guns required several men to operate them, and the six gun-crews started their training on seafront at Clacton-On-Sea, in Essex. Here, they were billeted at a newly built Butlins holiday camp. Arial targets would be towed along the beach by planes, and the gun crews would attempt to hit them, whilst trying their best not to hit the planes!

Off to Bonnie Scotland

Towards the end of 1942, the regiment travelled to Dalbeattie, in the Dumfries and Galloway area of Scotland. Here, they continued their training, firing their shells from the beaches at the targets into the Solway Firth. It was in Dalbeattie, that Jim met his first wife, Betty. They eventually married on the 23rd February 1943, but there was a problem, Betty was a catholic, and Jim was a protestant. So, she asked Jim to become a catholic, which he agreed to do, but this couldn’t be done straight away, due to Jim’s forthcoming deployment. The local priest allowed them to marry, but the ceremony took place in his study, not in the main body of the church. Jim officially became a catholic, about twelve months later, when he was confirmed at a church in Milan. They had no time for a honeymoon, as the regiment would soon be off to North Africa, on a troop ship from Greenock. Embarkation started on the 13th March, and sailed two days later, on Jim’s 23rd Birthday.

Jim and Betty were married for 32 years, until her un-timely death in 1975.

Invasion of North Africa – Operation Torch

The convoy consisted of 19 ships, which included 10 escorting Destroyers, Jim was on a Greek ship called the Nea Hellas. On 23rd March, when they were less than 100 miles from Algiers, the convoy was attacked by two planes, at approximately 2am. Both planes carried single torpedoes, one troop ship, the HMS Windsor Castle, was hit, but did not sink until around 5.30am. This gave three of the destroyers, precious time to rescue nearly 3,000 men from the stricken ship. Only one man was killed in the incident, but it could so easily have been many more.

Having docked at Algiers, Jim was detailed to take 40 men along the coast to Bougie to collect their Bofors guns and other equipment they needed. They didn’t travel by road to Bougie but sailed along the coast using troop landing crafts.

The 91st Regiment, was now part of the British 1st Army, commanded by General Alexandra. Their first action was when several planes were sighted, and all the guns opened up on them. Being very enthusiastic, and no doubt a ‘green’ bunch of men, the gun that Jim commanded ended up firing many more rounds than all of the others put together. When the officer came to check on how many rounds Jim’s gun had fired, he told him 106, the officer nearly had a fit, and was not best pleased with Jim. The other five guns barely shot 20 rounds between them!

Friendly Fire

The regiment left Algeria, and travelled to Tunisia where they took part in the final stages of the Tunisian Campaign. On one particular day they were ‘dug-in’ along the side of a valley near Tunis when the guns opened up on 3 single seater fighter planes which were flying low down the centre of the valley. Jim ordered his gun-crew not to fire as he recognised them as Hurricanes, not Messerschmitt 109’s. They were more bulkier than the streamlined 109’s, also the British Roundel (circular insignia), on the side of the planes, was clearly visible. After the firing had ceased, a bad-tempered battery officer came to see why Jim’s gun had not fired at the planes, so Jim explained why. But the officer was adamant they were 109’s, and told Jim he had not heard the last of it. The officer returned later, but with an apology, the planes were indeed Hurricanes, not 109’s. Apparently, the divisional HQ had been mistakenly shot upon these planes, so they had returned fire. Jim was proven correct in his judgement, but this ‘friendly fire’ incident, could so easily have turned into a disaster.

On another occasion, Jim and his gun-crew had a near miss when an enemy shell landed about 50 yards from their position. However, it exploded amongst a group of soldiers from the Royal West Kent Regiment, who had returned from the front line for some R&R. Unfortunately, several soldiers were killed in the incident, at the time they had been happily playing cards.

After months of fighting, the British entered Tunis in early May, and the last resistance from the enemy came in the Cape Bon Peninsula, where the Allies had trapped them against the coast. The refusal of Hitler and Mussolini’s to retreat from Tunisia turned out to be a fatal decision. This entrapment, and their lack of supplies, meant only one thing – the Axis were beaten. By the middle of May, the campaign in Tunisian was over, and with it, an estimated 250,000 prisoners, which including most of the Afrika Korps.

Tragedy

Following the Tunisian campaign, the 91st Regiment were ordered back to Algeria, to await their next deployment. This would eventually be Italy. Whilst in Algiers, the driver of Jim’s gun-crew was suffering from a terrible bout of piles, Jim was asked by an officer if he would drive the truck (known as a Gun Tractor), that towed his Bofors gun. He accepted the request from the officer, but Jim wasn’t an experienced driver at all, but he would give it a go. He had concerns about their ‘crash’ gear boxes, and the brakes weren’t servo assisted, so stopping these heavy-duty vehicles wasn’t easy. But Jim’s decision to take on the driving, would haunt him for the rest of his life.

In a convoy of six vehicles, Jim was driving down a steep mountain road, which had a sheer drop on one side. He started going too fast, and lost control, the Gun Tractor rolled over onto its roof. By sheer luck, there was a telegraph pole on the side of the road, which stopped the whole lot falling into the valley before. But the tragedy of the accident was that one of Jim’s crew was killed when the metal bar across the top of the windscreen, went into his chest, killing him outright. Jim never drove a truck again.

The Itailian Campaign

In March 1944, the regiment sailed to Italy, and landed in Naples, just as the nearby Mount Vesuvius was erupting. The major objective of the Allies was Rome, but to get there, they needed to overcome the Winter Line, which was a series of German and Italian fortifications across the country. The town of Cassino was a target of the Allies, but particularly the Benedictine Abbey known as Monte Cassino. It overlooked the town, and the Allies firmly believed that it was being used as an observation post. The Americans heavily bombed it, but most of the people killed, were apparently civilians. The ruins served only to give more cover for the defenders. Several gruelling months of fighting took place, with the Polish forces taking the brunt of the casualties. When Jim’s regiment arrived on scene, they took part in the fourth and final battle of the Abbey. The Artillery put down a heavy bombardment before the infantry went in on the final push. Both the Polish and British flags were raised over the ruins, on 18th May.

After Cassino, the Allies including Jim’s regiment entered Rome after the enemy had withdrawn from the city as they were being pushed into the north of the country. In July 1944 the new Italian government signed an armistice with the Allies. Mussolini however, continued to resist, and formed his own ‘Italian Social Republic‘, in the north of Italy. They fought alongside the Germans, but this new ‘government’, never amounted to more than being just a puppet state of Germany.

Regiment Disbanded

As a fighting unit, the 91st Anti-Aircraft Regiment, became inactive for several months, and eventually disbanded. The enemy’s threat from the air was now, non-existent. This meant all the men needed to find themselves other units. Whilst at a transit camp in Naples, the Parachute Regiment, were recruiting, so Jim decided to sign up for them. He travelled to a training camp near Rome, on the banks of the River Tiber, where he started his general training. Jim never got to do a parachute jump, so didn’t officially become a paratrooper. But after only a few weeks, Jim decided it wasn’t for him, so requested a transfer.

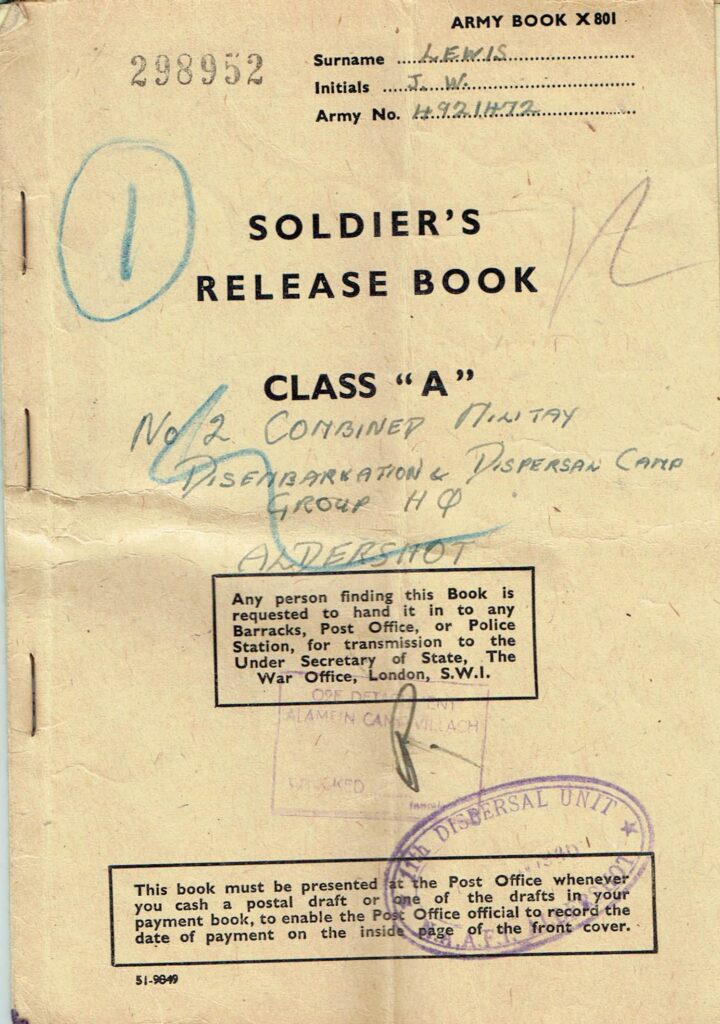

The German Army in Italy surrendered in early May 1945, and the war in Europe was over. Jim found a job as part of the administration staff of the 310 Transit Camp, in Milan. This was an ex-Italian army barracks, which was now a base for troops travelling back to the UK, on leave or de-mobilisation. Jim’s new appointment meant that he was transferred to another unit: The Royal Ulster Rifles/ London Irish Rifles, who ran the camp. He worked there for more than a year, until he returned to the UK, being de-mobbed at Aldershot barracks on 15th June 1946. Here, he was given a demob suit, and some money to see him on his way. ‘Jim’s War‘, was finally over, so it was back home to Kenilworth, and his old trade of painting and decorating.

Later Years

Later in life, he got a job in the paint-shop at Wickman Machine Tools, Banner Lane in Coventry, where he worked for over 30 years. He married his second wife, Josephine in the year 2000, and they lived in Northvale Close, not that far away from his former home in Watling Road.

Unfortunately, Jim died in 2020, two days short of his 100th Birthday, even though he had already received many ‘100’ cards from family and friends. Plus one, from Her Majesty the Queen, which was also sent to him a few days early.