In the graveyard at St. Nicholas Church stands one of the many large Sarcophagi, with the inscription:

‘In memory of John Bursell of Bickmarsh Hall, who was lost in the wreck of the Jersey Steamer Express September 20th 1859, aged 42 years‘

The Bursell Family

Over many decades the Bursell’s were a very prominent family in Kenilworth. John’s father Henry was the proprietor of the King’s Arms having purchased the property in 1813, which at the time was a busy hotel and the general hub of the community. John was born on 13th January 1817 and was baptised at St.Nicholas church on the 8th May. He had an older brother called Henry, who was born in 1814. When their father died in 1834 he left the King’s Arms and other property to their mother Mary. But a few years later and now into her 60s she transferred it all over to John and Henry. Both brothers were farmers, as well as now being Inn-keepers. When John eventually moved away Henry became the main keeper of the King’s Arms.

The Marriage

John married Rebecca Coldicott in her home village of Church Honeybourne near Evesham in January 1848. She was then 22 and he was 31. They began married life as tenants of Bickmarsh Hall, south of Bidford-on-Avon. According to the 1851 census, the farm consisted of 563 acres where 25 men were employed, plus four servants. They were happily getting on with their lives when they made the decision to go on holiday to the Channel Islands in September 1859, and from then on, everything would change……

The South-Western Company

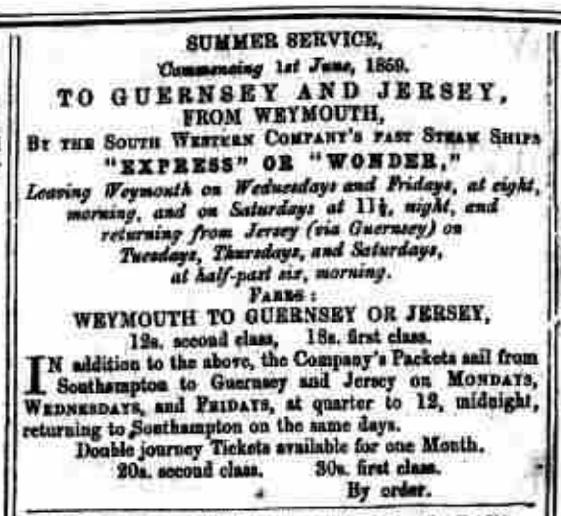

The Express was owned by The South-Western Company and was built in 1847, it was a twin-engine paddle steamer of 180 horse power and began life on the Jersey services. But after 10 years it started to operate the new passenger and mail service, along with sister ship Wonder from Weymouth to Jersey (via Guernsey).

It was in the early morning of 20th September 1859, when John Bursell, wife Rebecca and niece Jane Bursell boarded the Express on their return journey home from Jersey. In a misguided decision to save a few minutes of journey time Captain Mabb, who, at the time, was deputising for the sick Captain Harvey, steered a course he had never taken before. Departing St. Helier towards Guernsey it struck a treacherous group of rocks off Corbiere. Not realising the full extent of the damage, the captain continued on, but within a short distance the steamer stuck another rock.

A hole was torn in her bow and made water fast, but was able to limp-on but would not steer properly. With the ship slowly sinking, the captain and crew decided to head back to St. Helier. But it was clear they wouldn’t make it that far, so the steamer was steered onto some rocks at St. Brelades Bay. Reports indicated that John Bursell was helping lower a lifeboat when several passengers jumped into the boat, and he was somehow dragged overboard. Unfortunately he got trapped in between the lifeboat and steamer, and was soon overcome by the swell. Rebecca was reported to have seen the whole incident, shouting out several times, “My poor husband he is drowned”. Her life had changed forever.

150 Saved – But One Other Lost

One other man was lost in the wreck but all other passengers and crew of around 150, were saved. The women and children were the first to be rescued, followed by the men and the crew, Captain Mabb was the last off. The passengers were taken from the wreck to the land by second mate of the ship and Deputy Harbour Master, James Hanson who was on board as a passenger. Also on board were three race horses which were due to race at Guernsey the following day, and these were rescued by mattresses and bed linen being placed on the slippery rocks to enable them to reach land safely.

All the roads from the wreck-site to St. Helier were littered with stricken passengers, their luggage still to be salvaged. All the rocks and surrounding areas were covered with contents of the ship and passenger belongings. Rebecca and her niece were taken to the Tozer’s Hotel in St. Helier, where they had been staying during their holiday. Rebecca was reported to have been in a state of ‘bordering on distraction’. Captain Mabb was arrested and his Captains certificate removed.

Body Returned To Kenilworth

John’s body wasn’t found until the 7th October, and after more than two weeks in the sea it was unrecognisable. It was discovered floating offshore by a tug steamer that was laying down new telegraph cables between Jersey and Guernsey. The only means of identification was his cloths and personal items in the pockets. The family had left the island before his body was recovered, but Henry had left instructions that if his body was found, it should be sent to Kenilworth as soon as possible. His body arrived in a leaden shell on Sunday 9th October, accompanied by Mr. Thomas Kine of the Tozer’s Hotel. The burial took place on the following day at St. Nicholas. His grave, (plot 717), lies close to his mother and father’s grave (plot 730).

Coroner’s Inquest

At the coroner’s inquest the jury did agree that it was the body of John Bursell but they also concluded:

“That the loss of the Express was the result of culpable imprudence and ignorance on the part of Captain Robert Charles Mabb, then commanding the said vessel in her voyage towards Guernsey, by needlessly steering her through a dangerous passage, out of usual route, not having at the time, a pilot on board, not himself a pilot. And the members of the jury, strongly recommend the competent Authorities of the Island, in order to avoid greater calamities, to put into execution a law which enacts that every vessel leaving the island with passengers, shall take a licensed pilot on board”

The Board of Trade also held an inquiry but no verdict was reached. The crew and passengers were interviewed and there was no doubt that Captain Mabb took the wrong course at Corbiere called ‘Jailers Passage’. But the testimony of the witnesses was apparently contradictory. The magistrates could not decide upon the case. Chairman, Mr. Bernard said: “Under the circumstances it is difficult to know what to do. I cannot do otherwise than return Captain Mabb his certificate without expressing any opinion on the case. I have no power to retain it”

Captain Mabb had been with the company for about 20 years, and was said to be ‘prostrated’ by the whole incident and has since ‘lost reason’. The value of the Express was said to have been around £7000. (well over £400,000 in today’s money 1)

Bad Time For Sea Travel

There was no doubt it was a perilous time for sea travel during the 19th Century. ‘Health & Safety’ regulations didn’t seem to be much of a priority back then. In the Board of Trade’s Annual Wreck Register of 1858 it was recorded that on average, 745 people died each year during the period 1881 to 1858. In 1858 alone, 1170 vessels of various types, were wrecked.

The Will

Following his death, all the farm equipment and livestock at Bickmarsh were auctioned off. The executers of his will were his brother Henry and William Hiorns from Rebecca’s home town of Church Honeybourne. The value of his estate was recorded as being Less than £3000 2, not an insubstantial amount back then. We don’t know who were the beneficiaries of the will, as women’s inheritance rights during the mid-19th century, weren’t favourable, to say the very least. But it looks like Rebecca did benefit in some way, as census records indicate that she lived by ‘independent means’ for the rest of her life. In the 1861 census, she was recorded as being a ‘retired farmer’, she was then only 35 years old.

During their eleven-year marriage, they never had any children. (none that we know of). She soon moved away from Bickmarsh but continued living in the local area. On the 1881 census she was living with her nephew Robert Coldicott at the 350-acre Pastures Farm in the village of South Littleton, three miles from Bickmarsh. The farm employed 8 men, 3 boys and 2 servants.

Widow For More Than 50 Years

It would appear that Rebecca never got over the tragic death of her husband and she never married again, spending nearly 55 years a widow. She lived out the last few years of her life in Shipston-on-Stour, still living with her nephew. She died aged 87, and was buried in the town’s cemetery on 31st January 1914 3.